On keeping women skinny so they don't get too powerful

the patriarchy’s favourite weapon: keeping us thin and tired

Angels - this guest post first appeared over on

back in June, but honestly feels more relevant than ever right now!!! If you love reading about pop culture and the internet, may I suggest you head over and check out my sister publication??On keeping women skinny so they don't get too powerful

You’re not alone if you’ve felt the cult of thinness inch its way back into your periphery over the last few months. It seems even after around half a decade of body positivity and some major achievements in the diversity of body representation, the trend cycle has spun back to its faithful and true: thinness. Fuelled by the likes of the indie-sleaze renaissance and Ozempic, thinness is re-emerging as the body standard – worming its way back into the conversation with its best Madison Montgomery: “Surprise, bitch.”

In recent weeks, many creators have joined the choir of scholars who came before them in questioning the relationship between these always-changing body standards and women. While body standards prey on us all (gender identity be damned), they do predominantly concern themselves with enforcing a very specific kind of femininity. One that’s usually white, able-bodied and straight-passing.

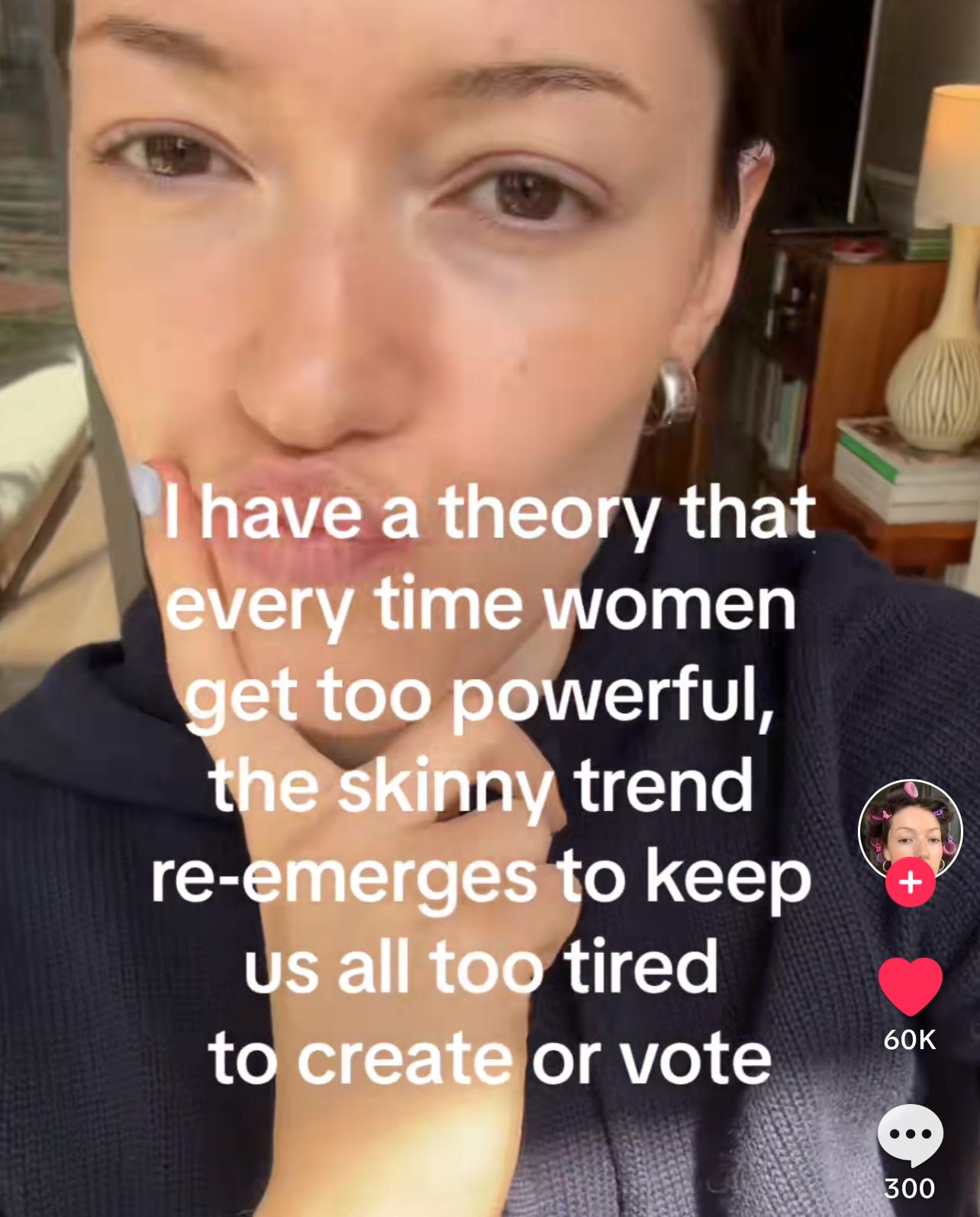

One creator even hypothesised that the skinny trend only re-emerges to keep women all too tired to create or vote. With body trends so embedded in the worlds of health and fashion, this theory that an overarching body standard – Big Skinny, if you will – is actually informing the media we’re seeing might seem like some foil-hat feminism.

But upon a bit of amateur sleuthing thanks to my public library membership, the skinny trend to tired-and-passive woman pipeline has legs.

Has thin always been in?

You’ve likely locked eyes with a Rubenesque woman in a museum before – one of the few places in the 2000s where you could see a non-super-skinny body that wasn’t being ridiculed by Michelle Bridges. Perhaps sporting a few glorious body rolls, full hips and plump face, her presence confirms that body norms have changed throughout time.

Represented through words like plump, corpulent, lean, gaunt and many more, it seems humans have a long tradition of categorising bodies – and more importantly, politicising bodies. In the ancient era, fatness definitely existed (shoutout to my girl Venus of Willendorf), but most classical cultures idolised athletics and balanced proportions. Women’s body standards tended to uphold a slender youthfulness (think Greek-goddess esc) as most desirable.

From there, body trends were entangled a lot of the time with fashion, class and religion. In the mediaeval era, a fuller and more robust physique was often admired as it signified that you were eating good and chilling out (and therefore, rich). But by the Enlightenment and the ages to follow, the concern for science and reason as well as discipline and morality would put the focus on lean bodies. Not to mention the age of empire bringing Western-thought into contact with more non-Anglo-European bodies would help emphasise a type of thinness and use it as a tool of white supremacy.

This very brief (and bastardised) history of the body reminds us that these trends are always changing and the body is political. It is a canvas for cultures to pin its systems and values.

Testing the women’s-power-skinny-return phenomena

Most of the understandings we hold today about the body stem from the Victorian era. Best known for putting kids in factories and obsessing over morality, the Victorians codified a range of social norms that we still see traces of today.

At this time, high moral character was trending and the era believed the body was keeping score of it. Thinness became associated with the highly valued traits of discipline and self-control, while any trace of fatness was linked with a moral failing, like gluttony, deviance and sloth. Sort of like how conservative media tends to pedal the idea that fatness is a sign of laziness and lack of self respect today.

This time also popularised a lot of today’s diet culture and how it created what would become modern eating disorders. Conveniently, the Victorian era also wasn’t too worried about the side effects from dieting (like extreme tiredness, mental fatigue etc.). Joan Jacobs Brumberg argued that women in this time would even “carefully conceal their appetite for food in fear that it would be misconstructed as a desire for sex” and subsequently, allude to sexual deviance and poor moral character. Because god forbid a woman be hungry and horny.

There’s no doubt beliefs of the Victorian era were the result of many complex things intersecting. But, this focus on thinness took flight just a few decades after Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published in 1792. For those unconverted, this text was a revolutionary touchstone in the birth of feminism (or, a feminism concerned with white, middle-class women).

Mary’s work advocated for the equal education, legal rights and sensibility of women, even looking to the emphasis society placed on a woman’s body: “taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.” While A Vindication of the Rights of Woman wasn’t being widely read by women (thanks to literacy rates); it pushed the question of women's rights to the forefront of the cultural consciousness. Ultimately, the Victorian era’s concern with women’s thinness was a by-product of a greater cultural movement, but its focus on order and tradition was definitely a reaction to the cultural change figures like Mary were championing.

If we look at history since this time, it’s hard not to see the relationship between women’s power and the trend of thinness. The pill was approved for use in 1960, giving women unprecedented bodily autonomy. Jean Nidetch would go on to found Weight Watchers three years later. Roe V. Wade passed in 1973. The decade to follow would be entrapped in a Reagan era conservatism as well as an obsession with women’s athleticism. ‘Perfect womanhood’ began to be associated with “hours of pumping iron in the gym” to draw from a 1986 Chicago Tribune article. The lolly-pop-head body trend of the 00s came after an explosion of girl-power media, an increase of women in the workplace and a fleet of legal reforms as well.

Now I don’t think there are some scary puppet masters out there pushing the skinny agenda from a bunker. But I do believe the systems of the patriarchy are so ironclad that they manage to correct themselves when too much change takes place. The phenomenon of traditional values growing more common after times of upheaval has been widely accepted in the context of war. And it seems that body trends follow a similar pattern when the order of gender roles is threatened.

But is skinny a right-wing conspiracy?

No. I’ll proudly go up against the Victorians and say that no body type should be shamed or moralised ever again. But the oversaturation of one very specific body type in our media does set a standard for women to conform. And in this case, it’s one that is unachievable for many and has historically triggered the rise of unhealthy (and literally, lethal) behaviours.

What this rookie history lesson has proven is that body norms are culturally constructed. They are never absolute. Never just ‘a given’. And never created in a vacuum. While the impulse to attain the beauty standard, and the acceptance they represent, is very human, perhaps we should be asking who really benefits from our bodies being trends.

Because I certainly don’t think it’s any of us.

who wrote this?

Kitty is a Meanjin-based writer and self-proclaimed pop culture fiend who’s obsessed with overthinking all things media. As a copywriter by day, Kitty writes words for some of Australia's biggest brands. By night, she channels her spiralling over the political undercurrent of culture into long-form writing. Find her occasional musings on The Lore of the Land and more yaps via the regrettable handle @sweetchillidoritos.

I don't think that keeping women thin makes them powerless. I think thinness tends to make a woman MORE powerful bc of how highly prized it is

thanks guys🫶🏻